Postcard by Heinrich Zille, 1918, photograph © Stiftung Stadtmuseum Berlin

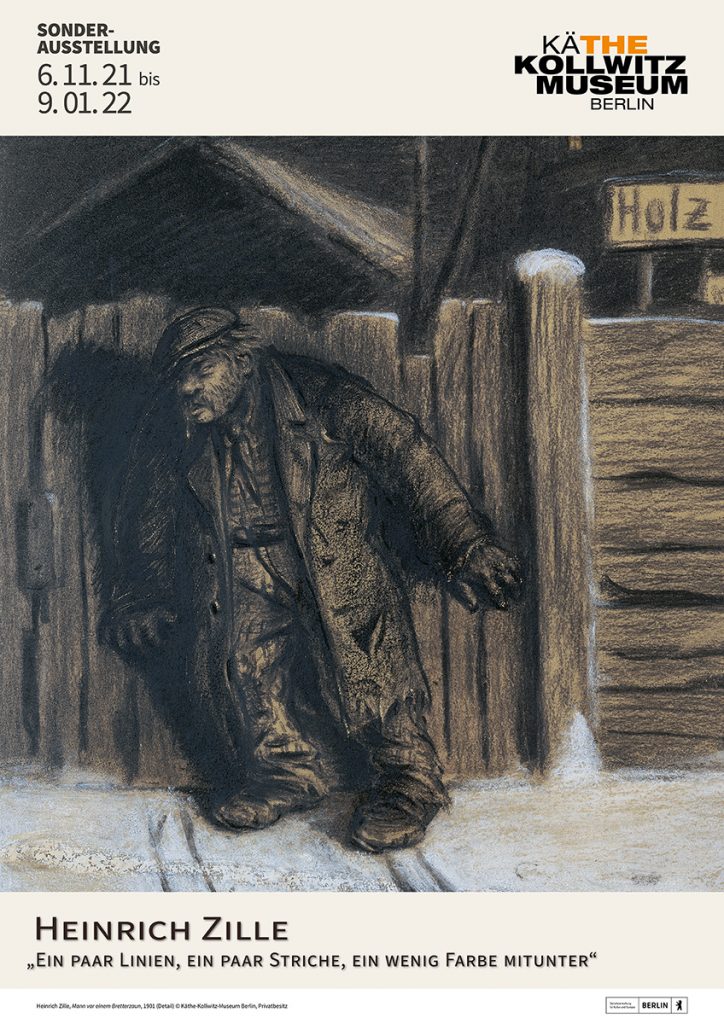

Special exhibition from November 6, 2021 till January 9, 2022

Though popular to this day, “Father Zille” still has a hard time proving that he deserves his place among serious artists. The joke-sheet illustrator and surveyor of milieus cultivated a reputation as an entertainer; this hurt the illustrator of Simplicissimus and the Lustige Blätter in the 1920s. Zille, creator of extraordinary sketches, had sunk into such obscurity that his appointment to the Academy of Arts in 1924 caused surprise and that a retrospective exhibition for his 70th birthday in 1928 introduced an unknown artist to most visitors.

Heinrich Zille first came to public attention as a freelance artist around 1900 when he participated in Berlin Secession exhibitions. His unsparing depictions of social misery closely hugged reality, and his drawings’ unusual style and composition immediately attracted the attention of critics. Prints and graphic editions published by Zille himself as well as his gallerist Fritz Gurlitt found their way to art lovers. However, Zille’s success with the general public, which continues to have an impact to this day, was achieved through witty drawings that dissolved his otherwise precise observations of social misery into many different stereotypical characters.

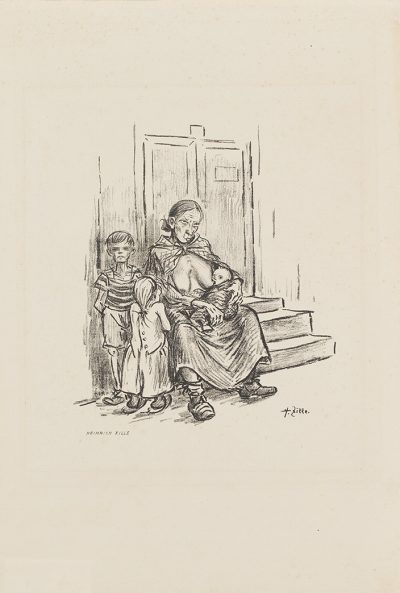

Heinrich Zille, Hunger, 1924, lithograph © Private collection

The sheet was part of the so-called Hunger-Mappe of seven original lithographs, which were sold for the benefit of the Internationale Arbeiterhilfe. Well-known artists such as Otto Dix, George Grosz, Eric Johannsson, Käthe Kollwitz, Otto Nagel and Heinrich Zille took part

The exhibition thus focuses on subjects that closely resemble those in Käthe Kollwitz’s work: the marginalized and those who lost out from industrialization and urbanization. Themes such as prostitution, alcoholism, unemployment, child poverty, and precarious housing conditions drove both artists in equal measure. Unlike Kollwitz’s work, the tragedy of Zille’s depictions often threatens to fade among his laconic and humorous captions. The Käthe Kollwitz Museum Berlin would like to use this exhibition to bring this “duo of great skechers” (as Fritz Stahl coined them in 1928) into greater awareness.

Sheets depicting the milieu in great detail are accompanied by his restrained colored works, which amply demonstrate Zille’s technical refinement. The quick sketches, on the other hand, show his skill in grasping form and movement.

At the end of the 1920s, Käthe Kollwitz wrote: “There is more than one Zille: one of them made illustrations for joke-sheets, and the other — I favor this one — is neither a humorist nor a satirist, but entirely an artist.”

On display are more than 50 works from a private collection in Berlin, including early, elaborately reworked prints, color etchings, color drawings, and pencil sketches.

Berlin’s Käthe Kollwitz Museum will move into its new location at Charlottenburg Palace in early summer 2022. Heinrich Zille once lived across from its theater building, on Sophie-Charlotten-Strasse, from 1892 until his death in 1929. This exhibition is therefore also our first step towards our new location.