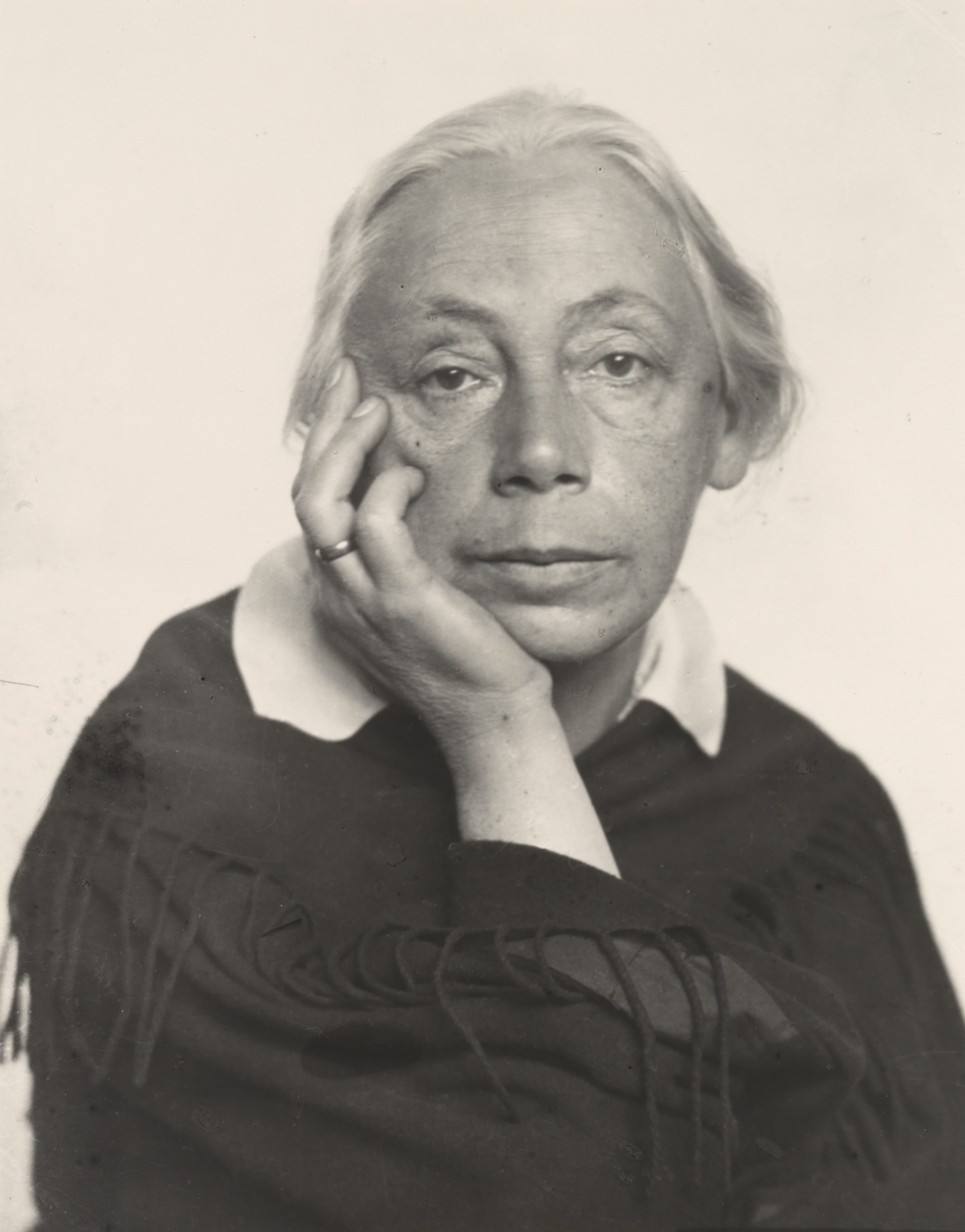

Käthe Kollwitz, 1925, Portrait by Hugo Erfurth

(in the public domain)

156 years ago, on 8 July 1867, Käthe Kollwitz was born.

On the occasion of her anniversary, we let Käthe Kollwitz herself have her say. On her 50th birthday in July 1917, the artist and pacifist born in Königsberg (today Kaliningrad, Russia) noted in her diary:

“It was my 50th birthday. So different from how I used to think of it. Where are the boys? But the day was beautiful, this whole time is beautiful. I am told from so many sides that my work has value, that I have achieved something, that I have exerted influence. This echo of life’s work is very nice, satisfying and gives a sense of gratitude. Also a sense of self. But at 50, this sense of self is not as dissolute and haughty as it is at 30. It rests on self-knowledge. One knows best where one’s own limits are upwards and downwards. The word fame no longer intoxicates. But it could have turned out differently. With all the work, success could have failed to materialise. Luck was involved. That it turned out that way, yes, I am grateful for that.”

In the Kollwitz family, fixed rituals were observed for each birthday, which Käthe Kollwitz lovingly recorded in her diary. For example, in July 1923, 100 years ago, she wrote:

“It was my 56th birthday. Karl decorated the table so beautifully early in the morning, 56 little lights burned, but only for a little while, then they were extinguished and should continue to burn next year. Beautiful presents, Ludwig’s Goethe, the black silk scarf, Heinz’s garland of dancing figures (…). At noon Helga and our Hans arrive, who gives me a beautiful collection of prose pieces collected by Hofmannsthal. Karl is so funny. He puts on his top hat and dances with me. We play ball, also read from Hofmannsthal, (from) Jean Paul the “Swedish Pastor”. It’s so nice for the four of us to be together: Karl to me, Hans and Heinz. Hans brings me some beautiful larkspur from his garden and a strawberry cake from Otty.”

Even under the National Socialist regime, the Kollwitz family held fast to these family rituals. But the artist suffered noticeably under the devastating art policy of the Nazi dictatorship and Kollwitz’s unofficial ban on exhibitions.

After her works submitted to an anniversary exhibition at the Akademie der Künste were removed at short notice in autumn 1936, the renowned Berlin gallery Nierendorf withdrew its commitment to an exhibition to mark the artist’s 70th birthday. The fact that the exhibition plans for her milestone birthday were to fall through took a heavy toll on the artist. In a letter to her friend Anni Karbe on 13.2.1937, she wrote:

“The last, most certain thing at Nierendorf (…) has now turned into water again. Cancelled – the reason is always the same. I really find it hard to get used to the idea that I, whose participation used to be counted as an honour, now have to keep quiet. Now, at last, I think I’ve understood.”

(In: Käthe Kollwitz, “Ich will wirken in dieser Zeit”, Berlin 1952)

Käthe Kollwitz spent her 70th birthday uncharacteristically not in Berlin, but in the spa town of Bad Reinerz near Breslau. In July 1937, she wrote a long letter to her daughter-in-law Ottilie Ehlers-Kollwitz, who was also an artist, from which we can also read the beautiful tradition of celebrating her birthday:

“And now my thanks for your gifts for the eighth. (…) And the big light of life, which we have been burning since 8 July 1931. Father had set it up in my living room with lots of flowers. Your beautiful gifts were lying there. (…) Hans, your notes from the children, Peter’s fabulous merry-go-round and the girls’ equally fabulous blanket. Then, in addition, the Mediterranean book and your dear letters – so much beauty – so much work embodied in everything – I thank you from the bottom of my heart!

The day before, Father and Katta had wandered into town together and returned mysteriously. Now there were two bottles of wine and a fountain pen, which Katta gave me with a funny little poem. (…) So the four of us celebrated the day in my parlour with a delicious meal (trout after soup, then roast chicken and ice cream) and the bottle of champagne.

Then we rested and then it was Lisa’s present: we drove up to the Hindenburgbaude (…) in a beautiful car. It was wonderful weather and the views of valleys and immense forests were so beautiful! In the evening we burned another light, this time really seventy (…). A round board, in the middle the big 70, all around small holders with little lights. We burned them on the balcony, they were consumed with tremendous speed, in barely a quarter of an hour the glow and brightness were gone. Then we were all tired and went to sleep, and when I woke up the next morning I had a satisfied feeling: so, now I’ve jumped over the seventy barrier!”

(In: Käthe Kollwitz, “Ich will wirken in dieser Zeit”, Berlin 1952)

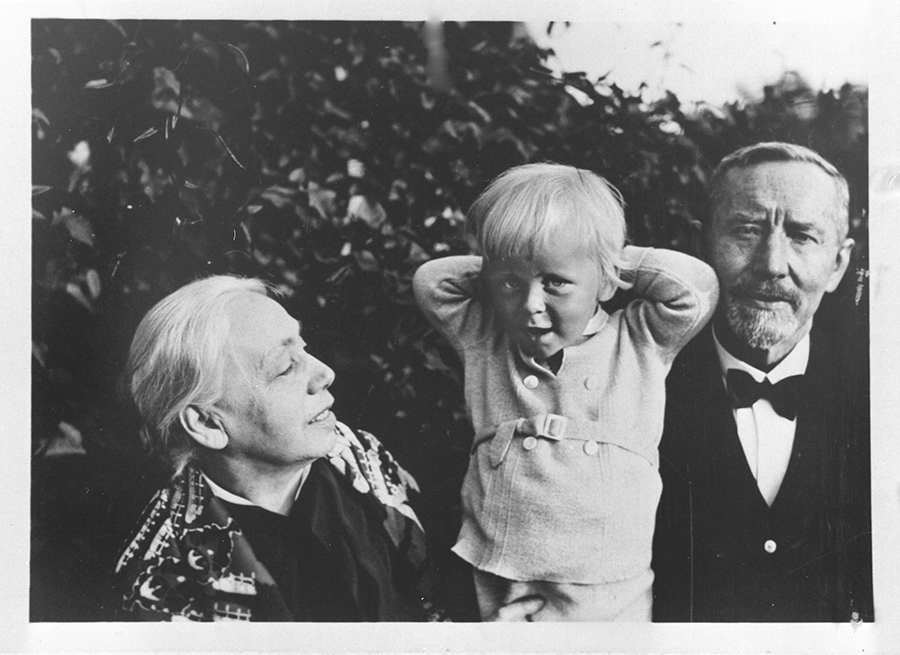

Each family member was allowed to enjoy similar beautiful birthday rituals. A tradition that was also continued for Käthe Kollwitz’s grandchildren.