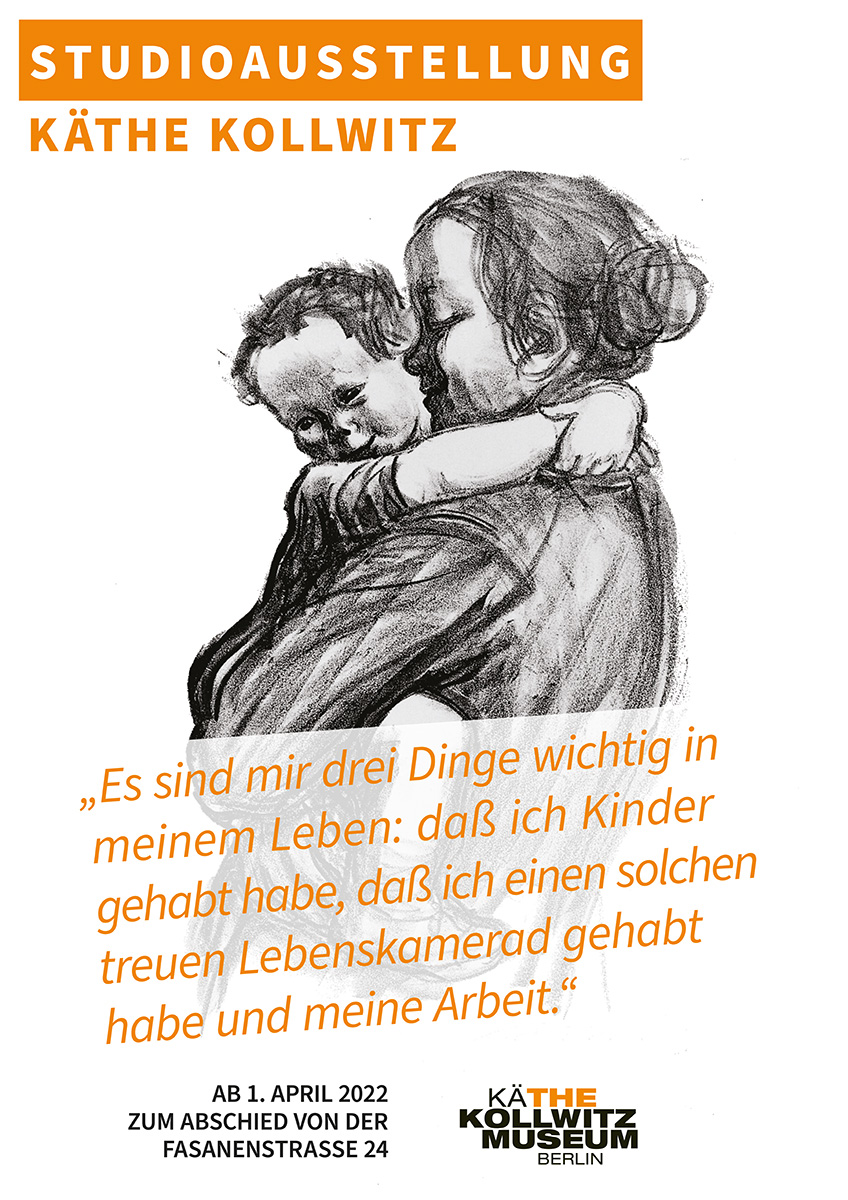

“There are three things important to me in my life: that I have had children, that I have had such a faithful life companion, and my work.”

Käthe Kollwitz to her son, January 1926

from April 1, 2022 until the end of June 2022

The last months at the Fasanenstrasse 24 location have begun and the museum is saying goodbye with works by Käthe Kollwitz on all three exhibition floors. In addition to the chronologically presented show on the life and work of Käthe Kollwitz, which shows the four large print cycles of the artist on the first and third floors, a differentiated view of Kollwitz’s art is possible on the second floor.

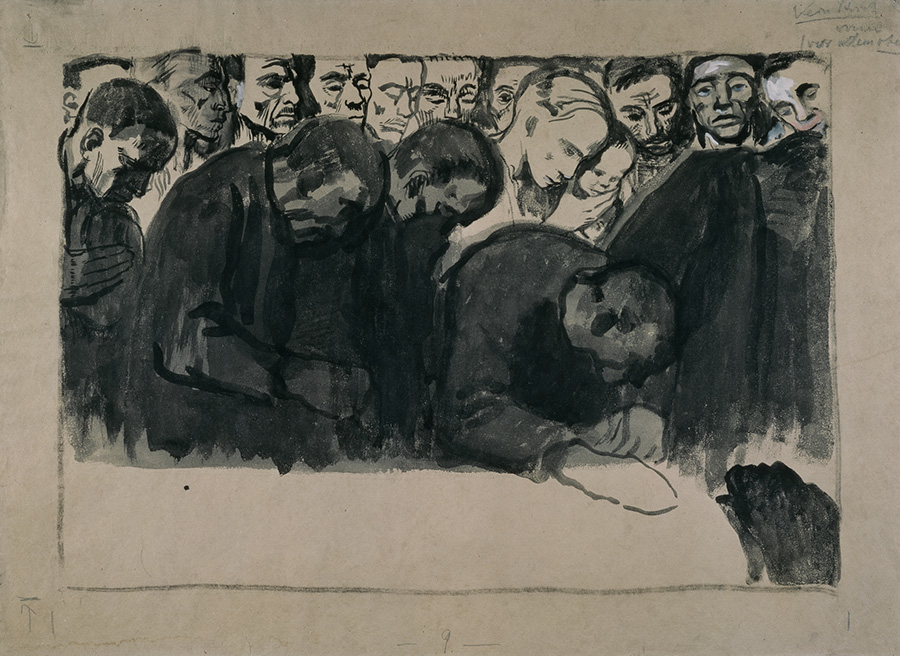

With study sheets, preliminary drawings, and proofs, the museum provides an insight into the artist’s workshop using the example of the “Gedenkblatt für Karl Liebknecht” (In Memoriam Karl Liebknecht) and shows her intensive involvement with the technique of woodcutting, which was new to her at the time.

The years after the First World War were marked by political conflicts and upheavals. The need among the population was great and hunger was omnipresent, especially in working-class families. Käthe Kollwitz began to get more involved in actions against hunger, war and poverty in the 1920s. She produced numerous posters and leaflets, including “Deutschlands Kinder hungern!” (Germany’s Children are Starving!) in 1923 as an appeal for donations for the Internationale Arbeiterhilfe Berlin (International Workers’ Aid Berlin) and the anti-war poster “Die Überlebenden” (The Survivors), published by the International Trade Union Confederation Amsterdam.

The artist had to painfully work out her clear stance against the war. At the outbreak of war in the summer of 1914, she persuaded her husband to allow their younger son Peter, who was not yet of age, to become a war volunteer. Many artists and intellectuals of the time joined in this war euphoria. For example, the gallery owner Paul Cassirer published a graphic magazine, “Kriegszeit – Künstlerflugblätter”. Initially appearing weekly, the paper published literary texts and lithographs on the events of the war, which completely followed the official pronouncements on the war and its course. Renowned artists of the Berlin Secession such as Max Liebermann, August Gaul and Ernst Barlach contributed to the publication. Käthe Kollwitz also contributed a lithograph and thematized the female view of the events of the war. Her work “Das Bangen” depicts the sorrows of women who had to let sons, husbands and brothers go to war. The print was published in the 10th issue on October 28, 1914, a few days later Käthe and Karl Kollwitz were informed of the death of their son Peter.

In the studio exhibition, the museum shows a small selection of the artistic works for the “war time”, including Liebermann, Gaul and Barlach, as well as fellow artists Dora Hitz and Hedwig Weiß

In the graphics of this period, Käthe Kollwitz addressed the precarious economic situation of many women and mothers who tried to keep their heads above water by working from home or were even dependent on urban shelter.

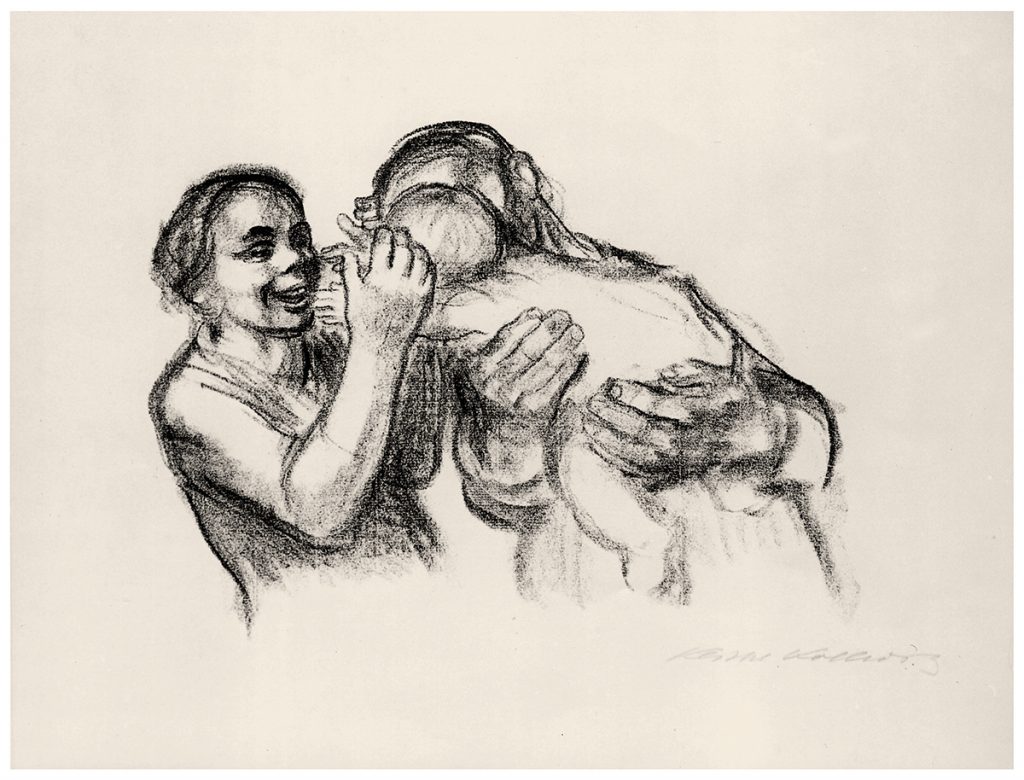

In addition to the often worrying motifs, the artist was also interested in the natural connection between mother and child – in loving togetherness, in everyday situations or while breastfeeding. Kollwitz brought the mother-child motif out of the two-dimensional drawing into the plastic, first in smaller groups of figures such as “Mother with Child over Her Shoulder” or “Woman with Child in Her Lap”, and finally in the large plastic group “Mother with Two Children”.

Family plays a major role in Käthe Kollwitz’s work, but portraits of her own family are less common. The artist’s works of her husband and siblings in her later years, which the museum presents together in the studio exhibition, are all the more impressive.

The artist repeatedly portrayed herself, so that there are a large number of self-portraits in a wide variety of graphic techniques and from all phases of her life. In addition, Käthe Kollwitz also inspired other artists to deal with her physiognomy. On the occasion of the farewell to Fasanenstrasse, the museum is showing portraits of the artist from its own collection, which others worked on of her. Among them is an impressive bust of Kollwitz by the sculptor Hans Breker, donated last summer by the artist’s daughter.